When a child is a key witness: Experts explain how sex assault cases unfold

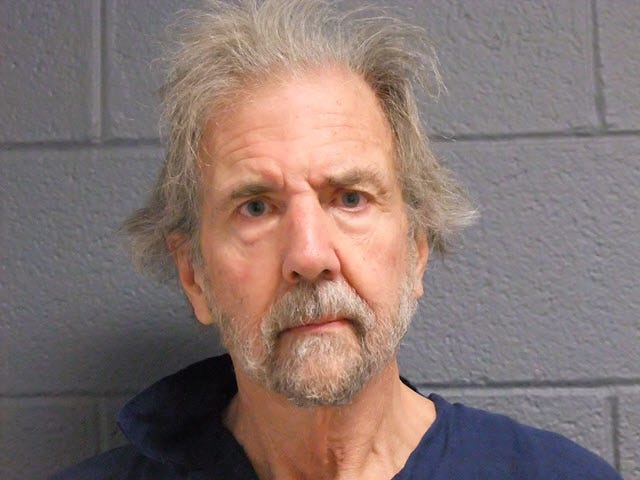

Bob Declercq of Grosse Pointe Farms is inmate 1087662A, held in Jackson

This exclusive coverage is intended to provide deeper understanding of criminal cases involving child sexual assault. The article is part of an exclusive series about the trial and conviction of Bob Declercq of Grosse Pointe Farms, Mich., a former wealth manager for Morgan Stanley and a prominent sailor.

Warning: This story — based on court testimony, court records and interviews — contains graphic descriptions.

*****

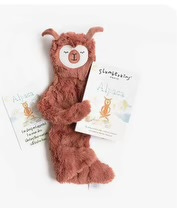

The 8-year-old girl wasn’t allowed to carry her stuffie with her when she took the stand in court. Those kinds of images can sway a jury.

Her tiny stuffed Alpaca, an emotional support toy designed for children with trauma, sat on the lap of the victim’s advocate from the state attorney general’s office during the child’s testimony.

For nearly two hours, a jury watched and listened as the 2nd grader answered questions from lawyers in the Oscoda County courtroom in Mio, located 200 miles north of Detroit, and 30 miles east of Grayling, in rural Michigan.

The child, wearing a heart necklace, didn’t see her mother or father in the courtroom. They were held in a family room as witnesses. She could see her older brother sitting with her paternal grandparents, supporting her truth.

At one table facing the judge sat an assistant attorney general and a Michigan State Police investigator. At the other table sat defense lawyers representing the child’s grandfather, a 71-year-old man on trial for two counts of sexual assault in the bathroom of his second home in Fairview.

The defendant testified on the final two days of a five-day trial.

Robert Allen “Bob” Declercq denied any wrongdoing. The defense portrayed Amy Declercq, a school teacher, as someone who put ideas into her daughter’s mind to punish her father for past sins.

Editor’s note: Amy Declercq gave Shifting Gears permission after the conviction to use her maiden name in news stories.

After the five-day trial, jurors found Bob Declercq guilty in less than two hours.

One by one, polled by the defense, the jury members each voiced GUILTY on two counts of first-degree criminal sexual conduct — vaginal penetration and anal penetration — of a person under 13.

The sex crime victim, at the time of the incident, was just 3 years old.

Lawyer Shannon Smith of Bloomfield Hills, Mich., who specializes in sex crime defense, told Shifting Gears after the May 2 verdict, “It’s very clear that the mother has some really serious mental health issues, the mother of the little girl who made the claims.”

Smith claimed her client didn't get a fair trial and he’ll win on appeal. After the sentencing hearing on August 18, Smith declined to comment to Shifting Gears. The defendant’s wife and son, who sat in the front row during sentencing, declined to comment, too.

The defense lawyer did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Appeals lawyer Michael Dezsi of Royal Oak, Mich., told Shifting Gears he needs to read the trial transcripts to determine what issues may be raised before he can comment on next steps.

Declercq retained the legal team to work on his appeal before being sentenced to a minimum of 25 years and up to 60 years. Circuit Court Judge Casandra Morse-Bills highlighted the defendant’s lack of remorse. Assistant attorney general Melissa Palepu described Declercq, a longtime sailor at the Bayview Yacht Club in Detroit and former sailmaker, as a “master manipulator.”

After the sentencing, Al Declercq of Grosse Pointe Park, texted Shifting Gears that coverage of the criminal case involving his twin brother lacked credibility, alleging responses provided by his niece were “written by a professional PR person.”

His niece testified in court under oath for approximately eight hours over two days.

A mother testifies

During this criminal case, the mother of the victim revealed details of her own sexual abuse involving her father. Those issues are being addressed in a separate criminal trial in Mackinac County in late October.

During the sentencing hearing, Amy Declercq spoke of her father as someone who engaged in a pattern of “emotional, financial and sexual abuse.” She turned to look toward her mother when talking of family members who failed to acknowledge and stop the abuse. She spoke in court about trading her silence and compliance for love and learning to disconnect from her body.

“I stand before you today not only as a survivor of years of abuse at the hands of my father, Robert Allen Declercq, but also as the mother of a child he has hurt. In truth that has devastated me in ways I cannot fully express. For most of my life, I carried the invisible weight of the trauma he inflicted,” Amy Declercq said.

“He convinced me that I was too much: too emotional, too dramatic, too anxious, too sensitive, too unlovable. That the pain I was suffering was my own fault … Now, as an adult, that damage still lives in me. I struggle with trust in friendships, in my marriage and in my workplace. I live with anxiety, depression and PTSD. To this day, I suffer from nightmares. Sudden sounds, unexpected touches or even hearing certain phrases can send me straight into a PTSD episode. I have been diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a chronic pain condition which my physician believes stems from the prolonged physical and emotional trauma I endured. I’ve attended weekly therapy for nine years and have only scratched the surface of healing from the trauma that I endured. I deal with the ramifications of my father’s abuse daily. But for our children, I was and am determined to be a parent so very different from my own. I have put in a lot of hard work, we set boundaries and we fought to build a life for our children that was stable and loving. My husband and I built a home for our children that was safe.”

“Despite our hyper vigilance, despite the safety rules my husband and I put in place from day one, despite my father never being trusted to be alone with my daughter, this happened because a family member, someone who knew my father’s history with me as a child, chose to ignore the danger exactly one time. Their negligence gave him access to her and he took his only opportunity to ever be alone with her and he assaulted her. Just like that, despite everything that we had/have done to protect her, the cycle repeated. When I found out, something inside of me shattered. No matter how much time goes by, I will never be able to put those pieces back together. My life, my family’s life and most devastatingly, our daughter’s life is forever changed,” Amy Declercq told the judge.

“… The guilt is overwhelming. Even though I know that I did not cause this, I feel I failed her. I thought I could keep her safe. Being a survivor is already a heavy burden. But parenting a survivor while still surviving yourself is almost unbearable. I sit with our daughter through her pain, through her nightmares through her fear. I know too well what she is feeling. That’s what hurts the most. I hold her while she cries, knowing there are no words that will undo what’s been done. I parent through my own heartache and triggers because my child deserves safety and stability in her moments of fear.”

“I’ve had to push down so much of my own emotion in the aftermath of her disclosure and throughout the court process because she needs me to help her carry her pain. As her mother, that is literally the least I can do. I tell myself I need to help my daughter be OK and then I can work on myself again. I mourn every single day for the childhood she has lost. The initial trauma caused by the assault is heartbreaking enough but then comes the anguish of a family being torn apart, the loss of relationships, friendships and trust. Mourning for people you loved who chose not to stand by you through the hardest thing you have ever had to do …” said Amy Declercq, looking at her mother and brother, seated together near the defendant.

“That betrayal will haunt me for the rest of my life. I am no longer that silent little girl. I spent way too many years keeping quiet to keep the peace for people who threw me, my husband and our children away the moment our daughter spoke out about the abuse.”

Moments of uncertainty

During the trial that led to conviction in May, court testimony indicated that Amy Declercq and her children were invited by her father to the family ranch during the COVID pandemic to care for her mother and ailing grandmother. At the time, Bob Declercq was living in Grosse Pointe Farms. He went up north to deliver groceries because he didn’t want anyone leaving the property, and he planned to remain in the hunting cabin on the 162-acre family compound. Witness statements disclosed that Bob Declercq went into the main house during the weekend the child was assaulted.

Amy Declercq had explained to her mother that the child, then 3, was not allowed to be alone with her grandfather ever. When Amy Declercq went to the bathroom in the main house and returned to the kitchen, she asked her mother where the child had gone — she wasn’t in the kitchen anymore. Court testimony indicted the child went upstairs with her grandfather to the bathroom. Amy Declercq ran up the stairs and encountered her father leaving the bathroom and her daughter naked on the toilet, not understanding why her daughter had all clothing removed to go potty.

Experts explain family secrets

After the Declercq sentencing, readers from metro Detroit and around the country reached out privately via email and text to praise the family for standing with the child and seeking justice — primarily sailors from different clubs, teachers, parents and grandparents who are primary caregivers.

The volume of questions I received highlighted many of the myths and misunderstandings about family sexual violence. I posed the most common questions to experts on these types of crimes:

Why would an adult survivor of familial sexual abuse interact with family

How could an adult sex abuse survivor allow her daughter to be in the presence of an alleged abuser

What explains a one-year delay of reporting the sex assault

Suzanne Dupee, MD., a forensic psychiatrist from Manhattan Beach, Calif., has served as an expert witness in child sex assault cases for two decades. She said sex abuse within families is not uncommon and carry with them complex psychological dynamics that outsiders find paradoxical and difficult to understand.

“When the perpetrator has power, either financial and/or emotional, the victim often continues to be psychologically and/or financially dependent on their perpetrator well into adulthood. Additionally, other family members such as their other parent might not believe the child and side with their perpetrator spouse by denying what happened because that parent puts their own needs before the child and might not want to give up the life they are accustomed to,” Dupee said. “The victim is essentially silenced and adopts that stance often for decades because other competing circumstances are stronger than them risking estrangement or ousting from the family.”

While the attachment between a child victim and a perpetrator parent is severely disrupted with the abuse, they continue to be dependent on that parent in the most primitive way -- to physically survive, Dupee said.

Forget and forgive

“The child's normal development is derailed and the child often tries to forget the abuse or 'forgive' because they have no other options, simply as survival mechanism. This creates a pattern of trauma bonding where the child maintains a pathological connection to the perpetrator parent and also often to the spouse who is in denial,” she said. “As the child grows into adulthood, confrontation of the perpetrator and other denying family members becomes increasingly difficult as time goes on because the perpetrator [falsely] believes that the victim has either forgotten, forgiven, or accepted the abuse …

“The victim often falls into patterns of learned helplessness, because no one believed them in the family, so ‘why bother.’ Learned helplessness becomes the prevailing psychological pattern the victim leads their life because their initial disclosures were met with rejection and possibly punishment or threats of being expelled from the family because it wasn’t believed or it will bring shame to the family. While victims realize what happened was wrong, they are powerless to confront the perpetrator, especially if the perpetrator has money and power. Social standing, if the perpetrator has high social standing, makes it even more difficult to disclose.”

Denial is an incredibly strong defense mechanism, Dupee said. “Victims often believe the perpetrators will not repeat the same behavior because they have 'learned their lesson' and will not reoffend. They also believe that other family members have 'learned their lesson' and won't allow the behavior to become intergenerational because they want to keep the deep dark dirty family secret and won't risk exposure.”

Adult survivors often blame themselves for 'letting' themselves be victims, Dupee said. “The vast majority of childhood sexual abuse victims sadly do not report their abuse for many years, often decades, if ever. They don't foresee that the perpetrator will reoffend because the situations are now different, i.e., the perpetrator is older with reduced or no libido, or the perpetrator wouldn't risk their career, reputation, or social status.”

Family systems exert powerful pressure on victims to forgive and forget, and the victim is unable to tolerate any other loss in their life, especially after losing their innocence, Dupee said.

Common to these criminal cases, she said, is the power imbalance between the perpetrator and the victim. Guilt and denial usually delay or prevent reporting.

“I knew of a case where a man physically abused the child, it was horrific, and the mom stayed because he had a job that could put a roof over their head,” Dupee said.

“For the child, it’s just too hard to lose everything. You’ve lost your innocence and now if you tell you’re going to lose your family. All these competing emotions,” she said. “A lot of people still love their parents even though they hurt them. Love is a hard thing to stop. And going up against your own mother is really hard. Whole communities hide this behavior, expecting children to keep it in the family and forget about it and move on.”

When love and hate clash

Elizabeth Jeglic, a licensed clinical psychologist and professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at City University of New York, serves as an expert witness in court on child sexual assault and grooming. She said conflict involving trusted family members creates emotional chaos for a child victim.

“He could be a great father in many ways but still an abuser. She can love parts of him but hate parts of him. It’s very difficult for children when they report the abuse and nobody does anything about it,” Jeglic said. “It’s almost like a learned helplessness, especially when it’s the non-abusing mother that does not support the child. Nothing is cut and dry.”

If children report abuse and it goes public, everybody’s life “blows up,” Jeglic said. “It’s not uncommon to never disclose … worried that the family will break up and nobody will believe the victim anyway. In many cases, a survivor may want their own child to have access to parts of the family. Victims are chosen because they are vulnerable. People who are supposed to be protecting you are not protecting you. And maybe the perpetrator has groomed family members to believe they’re a good person, and they may not recognize the grooming behaviors or interpret in light of - that is a good person – or that is a loved family member – they would not hurt a child.”

It’s easier to let things go when the harm has been done to you – but it is not so easy when it is your child, Jeglic said. “Delays in disclosure can be many, many years with younger children because abuse is understood within the developmental level of the child.”

How age plays a role in reporting

A child at age 3 may not understand that certain behavior is wrong, and later she learns information that helps her realize the need to share what happened, Jeglic said. “Young children don’t understand sexually abusive behavior. They don’t understand that people who are supposed to look out for them can actually hurt them.”

In more than 90% of reported child sex abuse cases, minors know their perpetrators and grooming is almost always a factor, Jeglic said.

“It’s a tremendous betrayal when a relationship is crossed and a child is abused by somebody that supposed to be protecting them,” she said. “You must let children know who is a safe person and that something will be done if they come forward and disclose. The worst thing for a child is when they make a disclose and they’re not believed or they’re believed and nothing changes.”

The reality in child sex abuse is that violation occurs in private and because children are often delayed in reporting, there is no physical evidence. So it’s the child’s word versus the perpetrator, and this makes it very hard to prosecute especially when the perpetrator has a good reputation in the community.

“One of the ways to defend against these charges is to attack the credibility of the victim. It’s a common tactic,” Jeglic said. “It’s why most child sex abuse cases don’t go to court. It’s horrible for the survivor and it’s re-traumatizing.”

Worse, she said, if we feel like people we look up to, people we value, are actually potential abusers, it makes everybody feel unsafe.

“It saves lives when people talk about this. Survivors must understand it’s not their fault. If somebody punches you in the face, you’re not ashamed. But when someone is sexually abused, it feels like a dirty little secret, but it should not as it is in no way their fault,” Jeglic said. “So much of this is psychological manipulation. People want the loving and caring part, they just don’t want the abusive part.”

Fallout

The Declercq case has been monitored closely within the national sailing community. Declercq is the son of a Great Lakes sailing legend whose boat “Flying Buffalo” dominated Port Huron to Mackinac Island races for years.

Members of various prestigious yacht clubs including Bayview Yacht Club in Detroit have called, texted and emailed Shifting Gears for months. Declercq was expelled by Bayview Yacht Club in May, after his conviction. He was also removed from the Bayview Mackinac Race Hall of Fame.

Heated discussion roiled Bayview, focusing on who knew about his criminal case and when. While the Mio property owned by Declercq has been used to host an annual Bayview board member working retreat in recent years, members have expressed shock publicly and privately after learning of the criminal charges.

Behind the scenes, sponsors of the high-profile Bayview Mackinac Race in July expressed concern about being associated with controversy. At least one sponsor requested that their name be removed from the race website.

The criminal conviction inspired discussion among metro Detroit yacht clubs and U.S. Sailing leadership to establish and/or improve safety protocols for reporting.

Declercq is currently held at the Charles Egeler Reception and Guidance Center (RGC) in Jackson, Mich., a quarantine facility responsible for intake processing of all male offenders, a Department of Corrections spokesperson confirmed to Shifting Gears on Thursday, Sept. 4, 2025.

The prisoner is 6-feet-3-inches tall and 180 pounds, according to his state file. His earliest release date is April 28, 2050. His maximum discharge date is April 28, 2085.

Editor’s note: Prison records list Declercq’s age as 71 with a birthdate of Nov. 19, 1953. Press statements from the state attorney general’s incorrectly listed his age and the spelling of the judge’s first name, which also has been corrected.

This is one of four articles examining the case. Read the first story with the defense perspective here. Read the second story with the victim’s family response here. Read the third story with the judge’s sentencing remarks here.

Elizabeth Jeglic, an internationally recognized expert in sexual violence prevention, sexual grooming and child sexual abuse, is author of: Protecting your Child from Sexual Abuse: What you Need to Know to Keep your Child Safe and Sexual Grooming: Integrating Research, Practice, Prevention, and Policy

PS: As a former political reporter at The Des Moines Register, I am honored to be part of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative, a roundup of news, commentary and features.

Exceptional reporting in an age when important events that are unpleasant are glossed over or under reported. Michigans Epstein files. It shines a light on a very dark side of society. It only highlights the adage - when you see something- say something. Exposes like this should spur action to help prevent abuse , and if that fails to to make exposure and strong punishment as a deterrent readily available

Ms Howard:

Your reporting on the trial , sentencing and comments from professionals in the child sex abuse field , let alone the sick man’s fun local boating affiliation, makes your series a Pulitzer candidate if not a clear winner.

You delicately exposed a local boating hero , family man, and investment advisor to be none of those!

What a story!

In my former life ( working as a Parole / Probation officer) I worked

with men who raped, abused, assaulted young children. Your

exposure of that sick man is very important for all to know exactly who he is.

Thank you .

Gregg