My aunt taught kids to read, believed in the power of libraries

Detroit school teacher talked about her students to the end

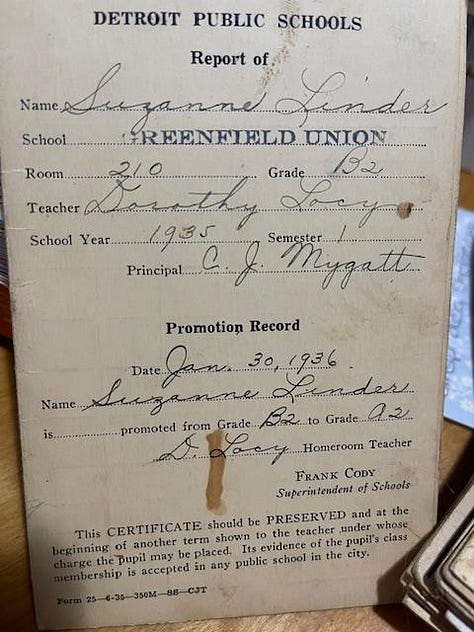

Suzanne Thelma Linder talked about her children at Schulze Elementary School in Detroit — second graders she taught how to read and write and fall in love with words— every week until her life ended.

The teacher had such beautiful handwriting and kept such precise records. Now it was up to me, her niece, to execute the final details of a life that began in Detroit, and ended in Grand Blanc 96 years later on Feb. 3.

My Aunt Poppy resented that her body quit before she was ready to go.

Smart, funny and fiercely independent, my Aunt Poppy was a news junkie who read The Detroit Free Press cover-to-cover and stood ready to debate every issue of the day. Not keeping up with news, she felt, was a dereliction of duty.

She was a proud union member and civil rights advocate. A fighter.

She believed helping children should be a top priority.

She told friends throughout her life that her favorite Christmas gift was a pair of shoes from Detroit Goodfellows, a charity founded in 1914 that — still today — is “making sure no child is forgotten.”

Aunt Poppy focused on friends, books, current events, needlework (embroidery, needlepoint, crochet) and Poodles. Her last Poodle, Madeline, died at age 17.

Aunt Poppy lied about her age. She didn’t want to be dismissed as an old lady.

Her favorite movie was “Pulp Fiction,” the 1994 crime film by Quentin Tarantino with Uma Thurman, Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta as Vincent “You Play with matches, you get burned” Vega.

She privately mused about shrinking from 5-foot-8 and dropping with age from a size 14 to a size 8.

Her skin glowed, makeup-free and so flawless that strangers would offer compliments.

“I can’t believe I had to wait until I turned age 85 to have nice skin,” she said after decades of skin issues.

She spent many years with a man her family assumed would walk her down the aisle one day. But he married someone else after attending a high school reunion. Aunt Poppy was not saddened by reports from mutual friends that he failed to live happily ever after. (He died at 72.)

She was a breast cancer survivor who counseled others through treatment, surgery.

Suzanne Linder — Aunt Poppy to family members, and a woman named Debbie, her favorite waitress at The Palace restaurant in Flint — was nicknamed after the flower in the yard next door to her house on West Hollywood Avenue near Palmer Park.

Poppy was one of the first words she said as a child. She loved wearing red, the bright color for which the poppy is known.

Born in 1928, Aunt Poppy was the fourth of five children. Money was tight.

Her father was a trolley car conductor. Her mother babysat the children of a wealthy Detroit family and rented rooms in the house to earn money. Helen Linder, who spoke German, Polish and Russian after making her way from Austria to America, actually polled her five children on whether she should divorce their father. They voted unanimously. He was prone to temper tantrums, breaking furniture and abandoning the family without money or food.

They kept their worn-out furniture covered in plastic. A picture of a man leading sheep hung on the wall.

Aunt Poppy’s mother spoke several languages including German, Polish and Russian after making her way from Austria to America.

At one point, two Detroit police officers moved into the house as boarders. They occasionally took Aunt Poppy and her little sister, my mom, for rides in the patrol cars with sirens blaring.

“That’s the kind of fun we had,” mom said, laughing. “We thought it was the greatest. A little offbeat, maybe.”

Campbell’s chicken noodle soup and Detroit cops

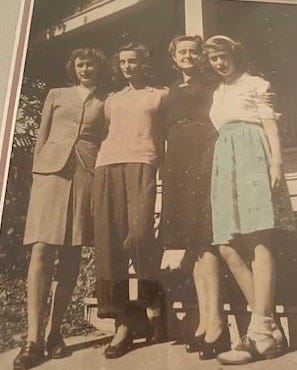

The children wore clothes sewn by my grandmother. Helen and Jacob Linder often dressed their two youngest daughters alike.

“We lived on Campbell’s chicken noodle soup and Franco-American spaghetti,” mom said. “I’m surprised we didn’t get rickets.”

Note: Campbell’s acquired Franco-American spaghetti in 1915, 13 years before Aunt Poppy was born.

Chasing a dream

After graduation from Pershing High School, Aunt Poppy took a job as a school secretary and spent nights taking classes at Wayne State University. She dreams of becoming a teacher. Her eldest sister helped pay for college.

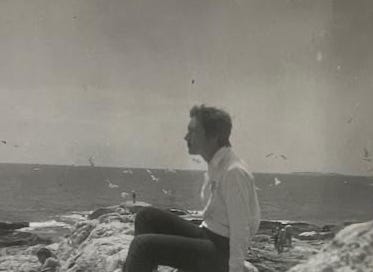

In the summertime, Aunt Poppy spent weekends at a cabin on Big Bear Lake in Otsego County, not far from Lewiston. She baked cakes and I read “Jaws” and “Gone with the Wind.” We’d curl up under her handmade afghan blankets

Aunt Poppy could turn strangers into friends. At restaurants in Flint, people would buy her breakfast or lunch for no reason at all.

“I can’t figure out why people are so nice,” she would say.

Reading books, every single day, Aunt Poppy would make recommendations to friends and strangers. The senior librarian at the local library sounded so sad when I called to say Aunt Poppy wouldn’t be checking out books anymore.

Every year, Aunt Poppy made a donation to the library. She felt reading was the single most important activity in this life. She talked about writing and writers always.

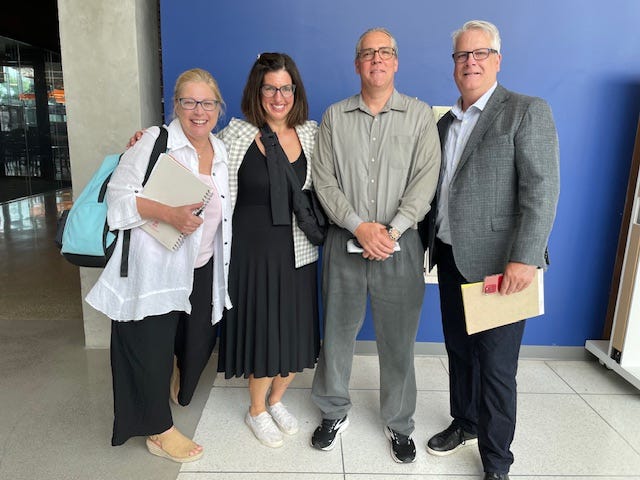

When I started as an autos reporter at The Detroit Free Press, Aunt Poppy sent all my articles about Ford Motor Company to her friends and neighbors. She would call and email and text. She was a one-woman subscription machine.

Aunt Poppy always wanted me to tell my colleague Eric Lawrence that she felt he was carrying the weight of the newsroom on his shoulders with his coverage of Stellantis — and Jeep, Dodge and Chrysler. She devoured stories by Jamie LaReau about General Motors. She asked questions about cars reviewed by critic Mark Phelan. And she really loved the humanity of our UAW coverage during strikes.

At first, Aunt Poppy said she couldn’t understand why anyone would want to write about cars. It sounded so dry and boring and awful, she said. Then the retired schoolteacher found herself opening the pages to read about cars first.

“I had to learn I loved the subject,” she said.

Saving her life

Aunt Poppy never traveled much out of Michigan. She saved her money. When she cashed out an investment, all she wanted was to hire a personal trainer.

And it saved her life.

In mid-November, when Aunt Poppy fell on her front porch, she was able to crawl back into her foyer because of her upper body strength despite a fractured pelvis, fractured ribs and severe pain.

She pressed the button on her emergency response necklace but nothing happened. She had worn that necklace around-the-clock for years. When she accidentally touched the button in the past, she had called to assure them she was OK. No issues.

19 hours

But Aunt Poppy remained on that tile floor for 19 hours. Every time she heard a noise, she thought an ambulance was coming, she said later.

“I was lying on the ground and I kept pressing it and pressing it and nothing happened,” she told me on Jan. 22, 2025. “It was terrifying.”

Finally, her friend Ed Henderson, a retired General Motors electrician from Flint, arrived to meet for lunch. He called rescuers.

After a stint in the hospital and months of rehabilitation with the love and support of her Poppy Posse — gym partner Ed, neighbor Leta Gonsler, personal trainer Kris Kotula, massage therapist Julie Kordyzon — Aunt Poppy built up her strength, trying to get back to her ranch-style home with walls covered in her own artwork.

But a series of setbacks disrupted Aunt Poppy’s wishes.

Then everything crashed.

Saying goodbye forever

In her final hours, my husband took her frail hands and asked, “May I have this dance?” He played Sinatra on his phone and sang bedside.

I remembered a 2014 documentary called “Alive Inside” about dementia and the use of music to reach people who appear to be far away. So I looked up the Top 10 songs for 1945 and hoped that Aunt Poppy would connect with the sound of her teen years.

We listened to Doris Day sing “Sentimental Journey,” — and then Perry Como, Bing Crosby, The Andrews Sisters and Sammy Kaye. Finally I played “Candy,” sung by Jo Stafford with lyrics by Johnny Mercer. It was a sweet, catchy tune. When I turned it off, I leaned over and whispered in my Aunt Poppy’s ear: “I have never heard of Jo Stafford. That song is fantastic.”

And we shared silence. Then Aunt Poppy, on her own sang quietly:

I call my sugar "Candy"

Because I'm sweet on "Candy"

And "Candy" is sweet on me

Those were her last words.

In memory: Books

Aunt Poppy requested no funeral service, no memorial and no obituary. She is survived by her sister, Elizabeth Wall of Fort Gratiot.

We made plans for cremation with the nice man at Swartz Funeral Home in Flint. Aunt Poppy would want anyone who loves words consider making a donation to Genesee County District Library — Grand Blanc/McFarlen branch, Book Fund, 515 Perry Rd., Grand Blanc, MI 48439.

In honor of Suzanne Linder, a reader to the very end.

Thanks for introducing me to Aunt Poppy. She is wonderful. Those sad, anxious hours you spent at her bedside helped shape a beautiful tribute. Your words remind us to share and honor love. Blessings.

Loved it! Thanks for sharing!