Black workers headed north to chase the American dream

How the Great Migration changed Detroit, our nation

While America figures out where the automotive industry is headed, part of the journey is reflecting on where it has been — not just the engines and metal but the people who worked to bring it all to life.

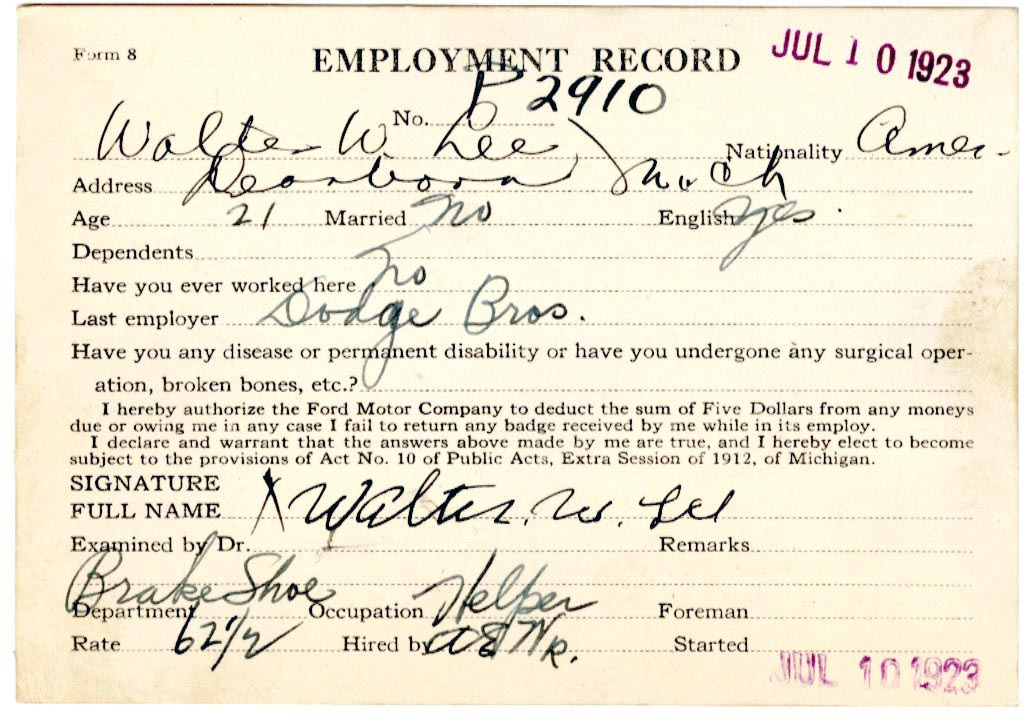

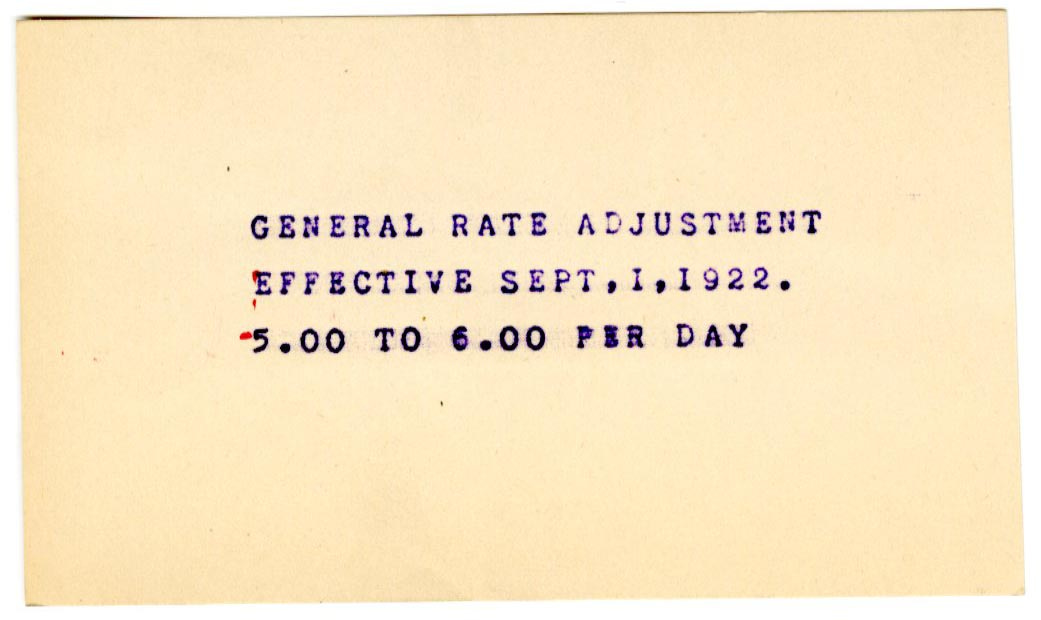

Incredibly, the population of Detroit doubled between 1910 and 1920, the beginning of the Great Migration — as Black people moved out of the South, Ford archivist Ted Ryan told me. Detroit was a magnet with Ford Motor Company known as a major employer that offered equal pay for equal work — a groundbreaking move in that era, he said.

“These aren’t just employee stories; they’re American stories. Each family’s journey mirrors the larger narrative of African American progress in the 20th and 21st centuries,” Ryan said in a statement. The archivist leads a team that keeps meticulous records, including photography and film, dating back to 1903.

Chicago grew by approximately 500,000 people, from 2.2 million to 2.27 million, while Detroit went from approximately 400,000 to nearly 1 million, he told me. “Can you imagine the impact on the city?”

On Thursday, Ford Motor Co. will host at Michigan Central Station a private sneak preview of the four-hour PBS docuseries, “Great Migrations: A People on the Move,” from Emmy-nominated executive producer Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr. It premieres on Tuesday, Jan. 28 on PBS and PBS.org.

While the series marks an important era in U.S. history, it is families in Detroit today who have lived the stories that reflect dreams fulfilled and struggle overcome.

These are their voices.

‘I’ve walked the land … It’s emotional’

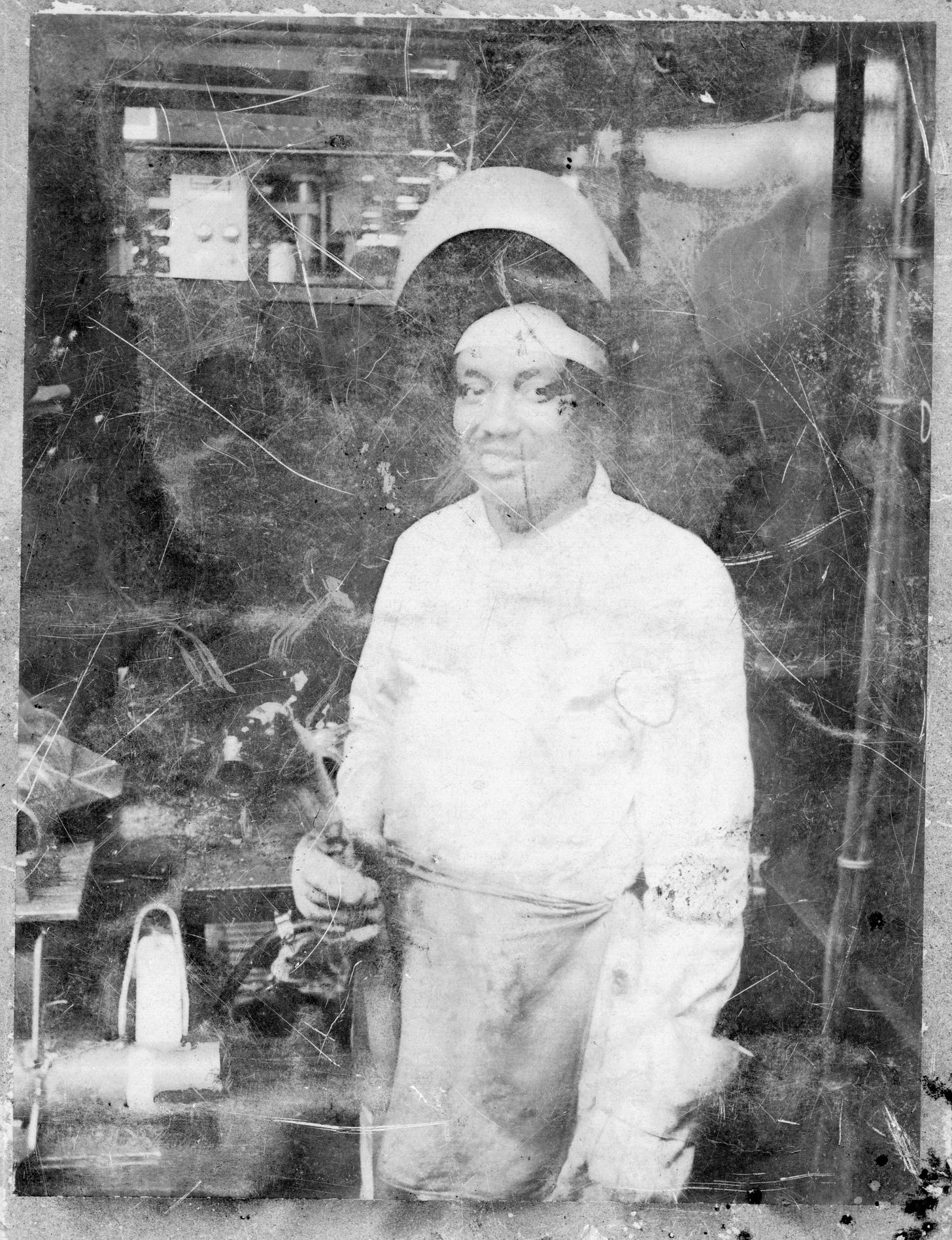

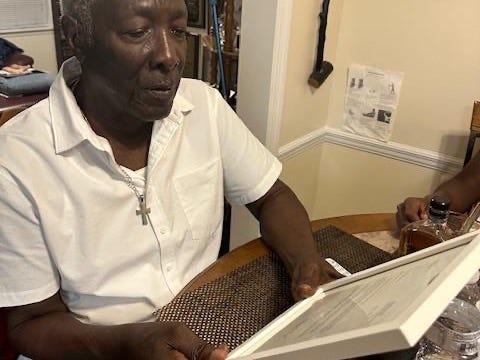

Paula Lee-Barnes, 59, of Redford, Michigan, is an executive assistant at Ford Motor Co. whose grandfather, Walter Ward Lee, moved from Clinton, Mississippi to Detroit to work in a Ford factory. He lived on Mullett Street in Black Bottom.

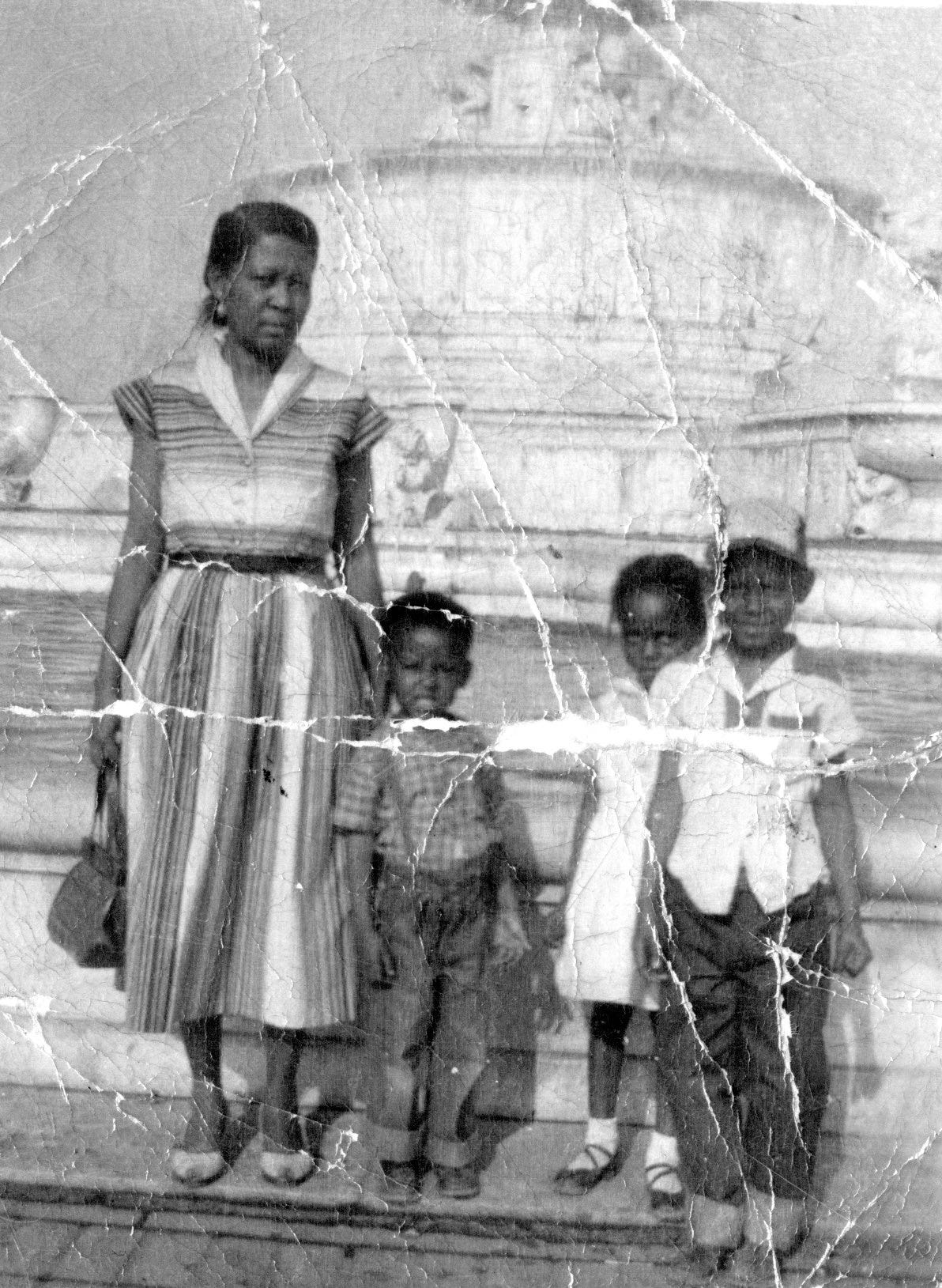

Her father, Charles, moved from Mississippi, too, and then his wife and three children came afterward. Five more children would be born in Detroit. The eldest brother, Charles, shares memories of stories about being very careful when leaving the house because 14-year-old Emmett Till had been lynched 100 miles north after being accused of whistling at a white woman.

Charles Lee II, now of Warren, Mich., would tell his little sister, it was “just so different” to go to school in Mississippi, she said. When Charles Lee arrived in Detroit, the family lived on Harrison Street, not far from Michigan Central and the old Tiger Stadium. They later moved to Williams Street.

Having learned about the past, Lee-Barnes loves to go back to Mississippi now.

“I’ve walked the land, the land my mother lived on,” she said. “I found Papa Ward’s headstone. He lived here and died here but they took his body back to Clinton, Miss. I have a whole lot of different feelings. It’s emotional. It’s fascinating. It’s exciting.”

Distant relatives who stayed in the south look forward to visits from Lee-Barnes. “When they find out I”m there, the term they use, ‘I can’t let you leave here without me laying my eyes on you.’ That’s what they say. They embrace me and they love me. It’s a wonderful feeling.”

She has walked from her mother’s childhood home to the nearby school, and attended the church her mother attended as a child. “I’m so blessed I can go there and feel the connection … Both my parents have passed away. All of my grandparents are passed away … To understand the sacrifices they made, the courage it took to come here. I know it was a struggle to live in the south. My dad, I think he was working as a mechanic, and working the land on a farm, but he saw that he had an opportunity for his family — My mother always talked about going back. She never did but she had it in her heart to do that.”

‘Becoming a middle class person’

Felicia Ford, 53, of Canton, Michigan, is an engineer who works on vehicles including the F-150 Lightning and Mustang Mach-E now.

Her grandfather, Roosevelt Ford, moved from Clinton, Mississippi. He started as a janitor and worked to become a skilled tradesman— a millwright who installs and repairs heavy and complicated equipment — at the Ford Rouge plant.

“Becoming a middle class person back in the 1920s as an African-American was pretty significant,” Felicia Ford said. “He was able to buy a house in Black Bottom and raise a huge family by any standard — 11 boys and one female who lived to adulthood.”

“My grandfather made a better life for his kids, encouraged them to get into the skilled trades,” she said. “My dad had a Corvette, a ‘72 Stingray, yellow with a T-top he bought used … I would be in the garage with him when he would change the brakes … He would allow me to test the brakes while he would stand outside and he would watch me … drive backwards and forwards when I was around 10 years old. I thought I was the stuff.”

She lived in the Magnolia neighborhood on the border of Southfield back then. Her uncles worked at Ford as a toolmaker, a model mold maker and electricians.

“I haven’t been to Mississippi,” Felicia Ford said. “I have to make a pilgrimage.”

‘The promise … while risky, felt worth it’

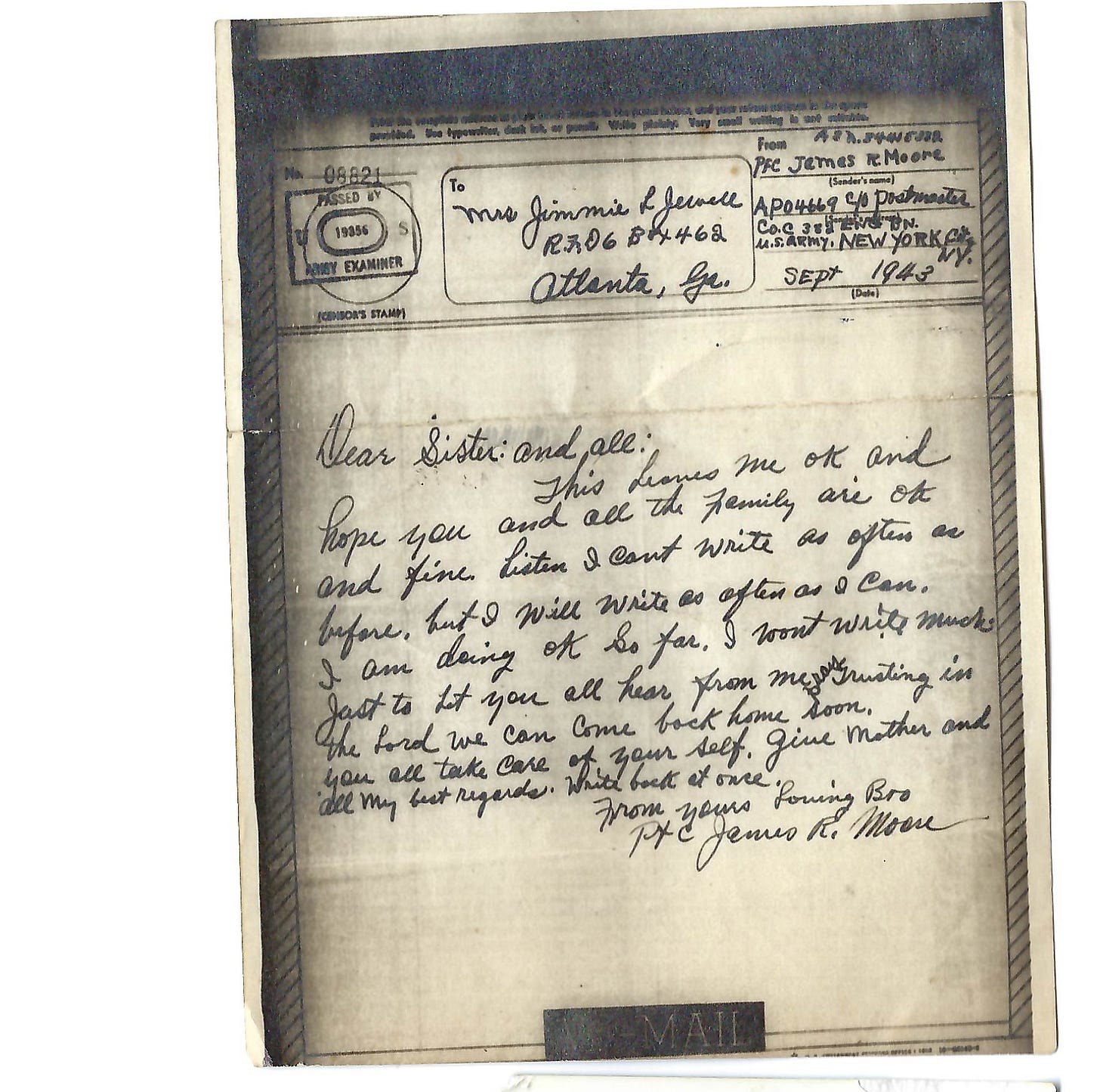

Clarinda Barnett-Harrison, 44, of Detroit, works for Ford as director of talent development and programming at Michigan Central Station. She works in the place that welcomed her mother’s great-uncle James Moore when he moved out of rural Georgia.

“He left World War II and really was in a position to think about how he would move forward in his life. He decided to venture out into the unknown and go to Detroit with no family or friends on the promise that he would get a job at Ford,” Barnett-Harrison told me. “It was very well known as a place that would provide fair wages to everyone and give most people an opportunity. In the late ‘40s, he moved to Detroit and did get a job (doing manufacturing and assembly work) at Ford.”

Going away to war and facing segregation upon return inspired soldiers to reflect on the American dream, she said. “The promise of being able to move somewhere, while risky, felt worth it. You knew what your reality would be in the south.”

Her uncle, Alfred Wayne Almond, moved to Detroit in the 1960s and worked at the Rouge plant, too, Barnett-Harrison said. “It took a tremendous amount of bravery to venture into the unknown and trust this promise made at the time — despite what was happening in the rest of the country.”

She, like her mother’s great-uncle and uncle, was born in Georgia. “It’s a really beautiful continuous thread … the 1940s, 1960s and 1980s.”

In 2023, Detroit’s population climbed to 633,218, marking the first time since 1957 the city has not lost population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

A family I loved as a child, not knowing their story

Patricia Taylor, 59, of Redford, Mich., is a manager of the SMART bus system in Detroit. She often flies to Valdosta, Georgia, to see her parents. Her father returned to his hometown after working at the Ford Rouge plant for three decades.

Claude Howard turned 90 in July, and Ford executive chair Bill Ford sent Howard a personal letter recognizing his contributions as a line foreman. A proud UAW member, he built the Ford Mustang and F-150 pickup.

He was working as a truck driver when he decided to pack up his wife and two kids in 1964, she said. “That was his whole thing, coming north, to provide and take care of his family. He built his life off of a third grade education. Yet my dad was one of the smartest men that I knew. He learned.”

Pausing to reflect, Taylor said, “He always talked about once he rested he wanted to move back home. He loved his hometown and it was just something he always wanted to do. He was always looking forward to it. So that’s what he did,” Taylor said. “But I guess his childhood friends and family, after so many years had passed, when he got settled, people moved or passed away. The life that he was looking for when he went back wasn't really there anymore. He kinda wished he would’ve stayed in Michigan, where he built a whole new life.”

Personal note: Patricia Taylor lived next to my father’s childhood home on Ward Avenue. I loved visiting my grandparents there, picking cherry tomatoes in their backyard. Tricia and I used to dance in her basement to the 1974 classic “Rock the Boat” by Hues Corporation.

We lost touch for nearly half a century, after I moved away, and recently met for dinner in Detroit. I never knew that her dad worked at Ford. I was the Ford beat reporter for seven years at The Detroit Free Press. I knew the Rouge and its factory workers.

I am humbled by the stories shared with me and honored to tell them.

Wow, what amazing stories of courage.

Phoebe, another highly informative article for sure! Oakland University History Professor Daniel Clark, PhD, specialization in American Labor History, has an oral history project where he speaks and records the experiences of Detroit auto workers who lived in the era of the formation of the UAW.

You may want to contact him to further discuss: DJClark@Oakland.edu

Kenneth Hreha

Oakland University alumnus, B.A. 2002

cum laude with Honors in History

Dan's Biography:

My main area of expertise is U.S. Labor History. My first book, Like Night and Day: Unionization in a Southern Mill Town (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), explored what unionization meant to workers and managers at cotton mills in a North Carolina community during the 1940s and 1950s. My second book, Disruption in Detroit: Autoworkers and the Elusive Postwar Boom (University of Illinois Press, 2018), argues that for ordinary autoworkers the period from 1945-60 was marked by job instability and economic insecurity, not a steady rise into the middle class. My most recent book, Listening to Workers: Oral Histories of Metro-Detroit Autoworkers in the 1950s (University of Illinois Press, 2024) is a collection of life history narratives constructed from my interviews with retired autoworkers. The goal was to provide a sense of autoworkers as full-fledged human beings, for whom jobs in the auto industry were one aspect of their complicated lives. Both of the books published by the University of Illinois Press are part of the Working Class in American History series.

https://oakland.edu/history/faculty-staff/daniel-clark/