As Tomahawk sank, T.K. Lowry said he couldn't fit into the life raft. His crew insisted: 'Get your ass in here'

Adam Lowry, a Rolex Yachtsman of the Year, sails Port Huron to Mackinac in memory of his father on the 40th anniversary of a terrifying rescue

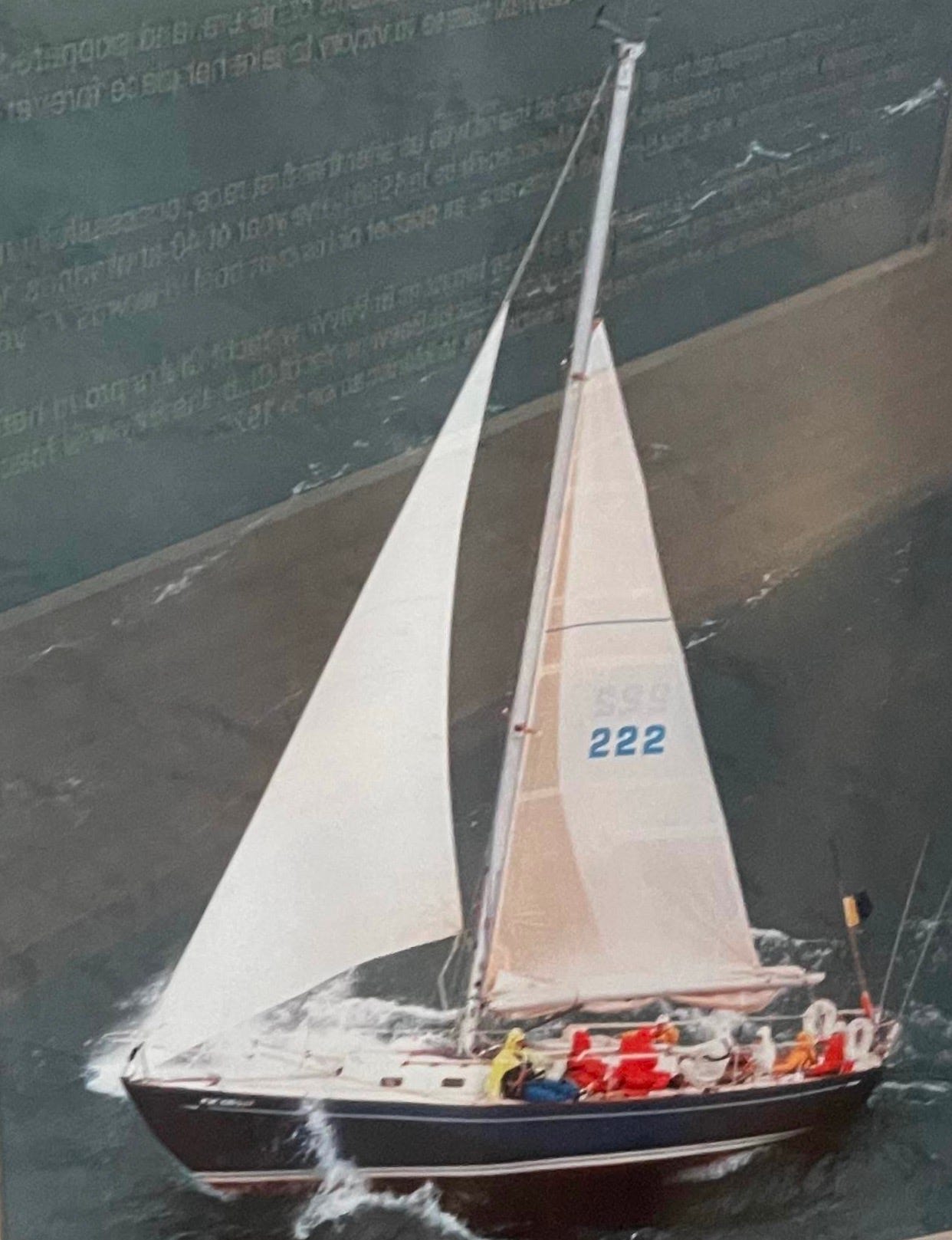

Tomahawk sailed into the darkness that July night, racing from Port Huron to Mackinac Island, fast and steady. When the wind suddenly spiked and temperatures plummeted to the 40s in an unexpected cold front, waves surged and pounded the sailboat. Then a crew member noticed a hole in the hull of the boat.

Desperate calls for help went out over the radio late Sunday, July 21, 1985.

Within 19 minutes of discovering the hole, crew abandoned ship.

Crisis ripped through the fleet during that year’s race. The National Weather Service reported 40 knot winds and 10 foot waves. In the end, 96 of 305 boats were forced to quit because of seasickness, torn sails and equipment damage including at least 10 boats with broken masts, according to Richard Bridge, Bayview Yacht Club historian.

While preparing for the upcoming 101st Port Huron to Mackinac Race this Saturday, July 12, 2025, many sailors can’t help but think about what happened.

“A 40 year curse? The thought has crossed my mind more than once,” said Tim Prophit, Bayview Yacht Club race chairman and skipper of Fast Tango.

(In 1945, just six of 45 boats that started in Port Huron actually made it to Mackinac Island because of vicious sailing conditions that left rigging damaged and lives at risk, Bayview archives said.)

The potential for a deadly outcome during this long distance race is real.

As of Sunday, 195 boats were registered for the Port Huron to Mackinac race, Prophit said.

Sailors think more about safety and preparation now. History serves as a warning.

“We were 25 to 30 miles from land in 350 feet of water. We thought it was over,” Pat Wright, 84, of Harbor Springs, Mich., told Shifting Gears. “The helmsman … was screaming ‘I don’t have a life jacket.’ The flare guns weren’t working. They couldn’t get the life raft inflated. It was very tense.”

Flares went up shortly after midnight on Monday, July 22, 1985.

Wright remembers Skipper Thomas Kirkpatrick “T.K.” Lowry of Grosse Pointe Shores, Mich., a 6-foot-9-inch former basketball player at West Virginia University, telling crew there was no room in the life raft for him.

Seven men were already stuffed into the emergency vessel meant for six.

John Garr, now 79, of Harbor Springs, recalled what the crew told their skipper: “Get your ass in here.”

Garr told Shifting Gears, “It was really dark. We were trying to get that life raft inflated. My anxiety level was such that I couldn’t concentrate to read the instructions on the flare gun. It didn’t make any sense.”

A series of complications on the C&C 35 sailboat kept the crew focused. A sailor carrying a Swiss Army knife handed it to Garr, who had to cut the life raft away away from the sinking vessel.

“This was like being in an elevator shaft,” Garr said. “The boat was underwater and the batteries still worked, so we could broadcast for help. The lights were still on when we pushed away from the boat and watched it sink.”

He remembers ice-cold lake water on his hands and arms, having tried to untie the knot that secured the lifeboat to the 35-foot sailboat before cutting the line. It sank 28 miles northwest of Tobermory, Ontario, Canada, near the half-way point of the 259 nautical mile race.

The water temperature was 50 degrees.

The U.S. Coast Guard reported being 8 to 10 hours away. Too far.

“Each member of the crew had a brief moment of silent thought with the knowledge that our yacht was going down. It was a moment measured in milliseconds. And it was a moment in which our thoughts were of death,” Wright later wrote for Sports Illustrated on July 14, 1986. “There was a helpless, desperate feeling as … I looked into the night.”

From First Place to DNF

Chuck Bayer, co-skipper of Old Bear, a Cal 36, picked up the mayday call on the radio. He set course following the latitude and longitude markings on the nautical chart — arriving within 60 minutes.

“The boat location in the northeast corner of Lake Huron was out of range for helicopters … They didn’t have the fuel capacity,” said Bayer, now 68, of Grosse Pointe Farms, Mich., and Vero Beach, Fla.

“We were forced to make three passes at the raft in rough water,” he said.

Old Bear didn’t hesitate to forfeit its first-in-class position on the race course.

“My father had just come off watch and woke me up,” Bayer said. “The waves were so big you could only see so far on the top of a wave and then you couldn’t see anything.”

When Old Bear reached the Tomahawk crew in the life raft, waves kept throwing the rescue boat sideways, Bayer said.

Once loaded up, everyone was sent down below for safety. Seasickness plagued the sailors, twice as many as the boat would usually carry. It took six or seven hours to motor to Alpena, Mich., Bayer said.

He and his father took turns driving Old Bear.

“Dad made me the co-skipper and navigator for that race. It was such an honor,” said Chuck Bayer, past commodore of Bayview Yacht Club. His father, Charles Bayer, was the first person to sail 50 Mackinac races. He died at age 89 in 2014.

Bayer: from Tomahawk to Jailbreak

This year, Chuck Bayer will race Port Huron to Mackinac on Jailbreak, a Farr 45, owned by Keith Cameron of Troy, Mich., and Shane Woolever of Sault Sainte Marie, Mich.

They — and all long-distance competitors — understand the risk on deep water with no one around for miles, often at night and sometimes in storms.

Bayer thinks often of Tomahawk.

“If we hadn’t heard them, they could’ve all drowned,” he said. “After that, everyone started thinking about our mortality a lot more.”

T.K. Lowry died in 2009 at age 67, before seeing his son named 2019 Rolex Yachtsman of the Year by U.S. Sailing.

That son, Adam Lowry, will race from Port Huron to Mackinac on Saturday in honor of his father.

“I was 10 when the boat went down. I remember my mom being pretty freaked out. We were on the island waiting for the boats to come in and it was really windy,” said Adam Lowry, 50, of Mill Valley, Calif., and Harbor Springs. “There was a report that the Tomahawk had sunk and the crew’s whereabouts were unknown.”

Incredibly, Adam Lowry wanted to race Mackinac that year and his father said the boy was too young at age 10. He began racing Mackinac at age 13.

Lowry joins powerhouse team on nosurprise

This week, Adam Lowry will crew on nosurprise, a 36-foot J/111 with co-skippers Scott and Merritt Sellers, of Larkspur, Calif., and Harbor Springs.

The father/daughter duo made headlines in 2022 and 2023 after racing in the double-handed category from Port Huron to Mackinac. At just 14, navigating the boat for hours under the moon to victory. Last month, Merritt Sellers, a senior at San Domenico High School in San Anselmo, Calif., won the Ida Lewis Trophy awarded by U.S. Sailing at the U.S. Junior Women’s double-handed national championship in Norfolk, Virginia.

Lowry, who grew up in Grosse Pointe Shores, Mich., and Sellers, who grew up in Birmingham, Mich., sailed at Stanford University together.

“We’re the next generation of sailors,” Scott Sellers said. “My dad raced against his dad. My dad, Bob Sellers, is 89.”

Looking back, looking ahead

Not all sailors competing this week knew T.K. Lowry, but they all know the boat.

Tom Vigrass, 69, of Port Huron, Mich., will race his 50th Mackinac this week on 50/50, a 32.9 foot X102 sailboat. He remembers hearing the Tomahawk call. Back then, he was young and fearless despite the rough waves, high winds and emergency call for help.

Now, with three of his own children on board, safety is more top of mind. But past drama doesn’t influence his plans or love of sailing.

“Time cures fear and you’re ready to go again,” Vigrass said.

Tradition usually means sailors owned up at the Pink Pony bar in the Chippewa Hotel on Mackinac to celebrate after crossing the finish line, and 2025 will be no different, Lowry said.

From sinking to victory

The year after the sinking of Tomahawk, T.K. Lowry purchased a C&C 39, named it Tomahawk and won first overall in Mackinac. Beth Lowry joined her father that year at age 18, and spent the next three years racing to Mackinac.

Neither Beth Lowry of Grosse Pointe Woods, Mich., nor her brother Thomas Kirkpatrick Lowry III of Charlotte, North Carolina, will race this year.

These days, the Lowry family hosts an annual junior sailing regatta out of Little Traverse Yacht Club in Harbor Springs to help build the sport, and keep the Tomahawk legend alive.

“Most people think sailing is a country club sport for rich people,” Chuck Bayer said. “It’s a dangerous and athletic and demanding sport. People don’t realize that. People have died ...”

These days, many racers consider the Sterling Silver Old Bear Trophy to be the greatest honor bestowed by the Bayview Yacht Club. It recognizes individuals who show support, dedication and an outstanding contribution to the Bayview Mackinac Race.

“Sailboat racing in the summer epitomizes all the great virtues of life — bravery, courage, competitiveness and trusting in the people around you,” Bayer said. “Just … finishing the race is similar to a marathon. It shows stamina, strength and endurance.”

The Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Belle Isle in Detroit now features the exhibit “Challenge These Waters: A Century of Sailing Detroit To Mackinac Island.” On display until Aug. 10, 2025, the collection includes artifacts from the Detroit Historical Society, Bayview Yacht Club and individual families, spotlighting events including the Tomahawk rescue.

Phoebe Wall Howard, a Grosse Pointe native, covered sailing for The Detroit Free Press for seven years, until 2024. Find her recent sailing stories here.

I was there. I signed on to keep an eye on my dad, Dennis, as it was his first Mac Race. Helluva deal! Yeah, the water was warmer than the air - it was 39F at Alpena that night. I figure the water was at least 45. I'm surprised it's reported as high as 50. I had just come off the helm as we'd decided to do a 'full court press'. I figured I'd better get some dry clothes on. My dad was taking the 10:30 nav fix when I heard the 'CRACK' instead of a thump. We'd split pretty much gunwhale to gunwhale across the leading edge of the keel. John Garr came forward to get some safety gear and a life jacket for Bernie Tenowski (the helmsman at the time) in ankle deep water. He went back in knee-deep water. Things were reasonable hopeful, despite the flare failures, until Tommy shot the last flare - the parachute flare. It incandesced in the barrel and we'd JUST finished inflating the raft. A ball of burning magnesium was not something you'd want near the raft!

This story is great reading, even for armchair sailors.