A diary from 1979 reveals how Chrysler dodged bankruptcy with Jimmy Carter's support

Factory workers, auto executives pleaded for help

The tipster at a luncheon in Washington, D.C. demanded discretion. A discussion that needed to take place would happen only on the condition that it remain a secret.

Topic: The financial unraveling of a Detroit automaker. At risk was not just one automaker but all three. Impact on the industry would be devastating.

Jim Blanchard, then a young congressman from Michigan, accepted the conditions presented by a source within the U.S. Treasury Department who revealed that Chrysler Corp. was in trouble, and the situation was worse than anyone realized.

Chrysler officials were engaged in behind-the-scenes talks seeking billions of dollars in aid.

The treasury official shared the confidential information with Blanchard in June 1979 because the official thought Blanchard was the one guy who could lead a rescue effort. The Democrat from Pleasant Ridge sat on the powerful House Banking Committee, which decides who gets government bailouts.

“I learned confidentially that Chrysler was visiting the U.S. Treasury Department and trying to figure out how they could get some financial help because they were having financial trouble,” Blanchard revealed in an exclusive interview.

“I was not supposed to know that, but I had someone at Treasury, who was a dear friend, let me know because he said, ‘If there’s going to be any rescue for them, it’s going to have to come from your committee.You’re going to have to deal with it and probably have to lead the effort. It’s a long shot and their problems are worse than they realize but you’re going to be the guy if they’re going to get help.’ But I can’t tell anyone until it becomes publicly known. So here I am, sworn to secrecy but knowing I’ve got to get ready for something really, really big.”

This is the untold story of historic events that unfolded under the leadership of Jimmy Carter, a nuclear engineer who served on submarines and destroyers in the U.S. Navy but campaigned for president as a peanut farmer from Georgia He died Dec. 29, 2024, at age 100.

Blanchard said the former president rarely discussed his accomplishments publicly, and he should have. Blanchard, now 82, talked from his law office in Washington, D.C. about the legacy of the 39th president and its direct impact on the Motor City.

‘As a favor to me, stay neutral’

Carter’s White House staff provided strong support on issues that required bipartisan support, especially those related to finance.

Why the unusual comments from inside the Treasury Department? Blanchard had worked on the New York City loan guarantee in 1975 as a freshman member of Congress on the banking committee, so Washington insiders knew Blanchard had experience.

But this latest problem wasn’t government helping government, it involved a private company. (Note: There was precedent. In 1971, Lockheed begged Congress for a bailout, saying the company’s uncertain status presented a national security risk. Their request for loan guarantees won support.)

But an automaker could not be compared to a defense contractor, Blanchard said.

Still, he would remain on standby for news to break.

It all unfolded while Blanchard was on vacation at a family cottage in Grand Bend, Ontario. He knew he had a tiny, rapidly closing window to keep a potential disaster for Michigan from unfolding on his watch. He got on the phone and called every Democrat on the banking committee. When he asked if they’d heard about Chrysler, the response was grim.

“I said, ‘Look, just don’t take a position. I think we can make a case to help them. But I’m not asking you to go out and agree to that. I’m asking you, don’t take a position on legislation. It will probably have to be a loan guarantee. As a favor to me, stay neutral,” Blanchard said. “When we get back to Washington in September, I’ll talk to you all about it.’ And they all agreed.”

‘There was no sympathy’

The fight to save Chrysler was going to be brutal.

“They said, ‘OK, but this looks like a real loser. It won’t be very popular where we live. Nobody cares about the auto industry. It’s all Michigan,’” Blanchard said. “I said, ‘Just stay neutral.’ You know what they did? They just stayed neutral. They did me a big favor. When we eventually developed the legislation which was in the Fall, and we eventually voted on it, I not only was the lead sponsor on the banking committee, I had strong committee support, including 13 proxies — that is, people who couldn’t be there but gave me their proxy. If I hadn’t made all those calls early to keep these guys from taking a public position against it, I don’t know if I’d ever got the bill through the committee. It had to get through the house banking committee first before it went to the full House and it would have to get through the full House before the Senate would even agree to take it up … It was a very unpopular thing.”

Between August and late December, Blanchard worked with Democrats and Republicans to get the rescue package approved.

The story made the news every single night.

"Truth is, when it surfaced in late July that Chrysler was in trouble and they were hoping to get some federal help, there was no sympathy,” Blanchard said. “There was a whole big groan, like, ‘Oh, the U.S. auto industry? They fight everything, they’re not as good as the imports and Chrysler doesn’t have good fuel economy.’ It was like, ‘Wow, fat chance we’re going to help them in Washington.’”

While the company, its car dealers, factory workers and white collar engineers were all urging Congress to back Chrysler, news outlets aired interviews with people who denounced the auto industry and criticized the company as unworthy of a government loan.

Carter wasn’t big on the idea of corporate bailouts

Yet the team at U.S. Treasury knew that the potential for harm to parts suppliers and the ripple effect on Ford and General Motors. Not only did Chrysler have 80,000 direct employees, but the Congressional Budget Office estimated hundreds of thousands of indirect jobs related to the auto industry could disappear.

While Blanchard urged the public to have faith, Treasury Secretary G. William Miller was not thrilled with the idea of a corporate bailout. He was apprehensive about taking the lead.

“Carter, himself, was a guy that really wasn’t into corporate bailouts, but I think he was practical. And his staff was very sympathetic,” Blanchard said. “I worked closely with Carter’s staff and kept him apprised of what I was doing. Treasury kept saying, ‘We need time to figure out how to do this.’ But we were running out of time.”

As news reports worsened by day, Chrysler sales plummeted. Dealers reported that foot traffic had stopped. Workers worried about job loss. Customers feared for their warranty coverage.

“The psychology of ‘let them go broke’ was really hurting the morale,” Blanchard said.

Members of Congress weren’t excited about voting on the controversial issue.

“The left wing said, ‘We shouldn’t help them because they make the wrong kind of cars. All the U.S. companies are really no good. They’re not fuel efficient.’ Then the conservatives were saying, ‘We don’t believe in bailouts.’ The left and the right wing were useless. They approached it from the point of view of ideology,” Blanchard said. “Whereas, the rest of us were trying to look at practicality. My arguments were, number one, Chrysler has got 80,000 employees in Michigan. They’re the largest employer of African Americans in the U.S. The spinoff is probably 360,000 jobs. It will ripple through the economy and be destructive. I’m not here fighting for a corporate insignia. I’m fighting for the people, the jobs, the families and the impact on communities.”

Lee Iacocca steps into the spotlight

When the dealers started calling members of Congress, things started to turn.

“This was the major auto issue of the time — whether the government was going to help Chrysler or not,” Blanchard said. “It was the major auto issue of that decade.”

Chrysler CEO John Riccardo, who requested the government loans and helped recruit Lee Iacocca, stepped down from his role in September 1979.

“Iacocca had been walking in the wilderness, having been relieved of his job (at Ford) by Henry Ford II,” Blanchard said. “Iacocca jumped right into the battle.”

Blanchard spent hours preparing Chrysler executives for congressional testimony.

“Ultimately, I talked to Lee Iacocca, between September and December, almost every night at 6 o’clock to review the day’s bidding. It was, ‘What did I want him to do’ or if he had suggestions for me. I don’t know what we would have been done if there had been social media.”

Car sales were drying up

They held week-long hearings, coordinating among Chrysler and the UAW. Iacocca was the first witness. (Widely credited with saving Chrysler from going out of business, he served as company president from 1978 to 1991 and CEO from 1979 until the end of 1992.)

“We had to convince the Chrysler family of workers and people all over, that we could get this done, that they were going to have a future. We couldn’t let the media talk us down. The sales were drying up. It was really bad,” Blanchard said. “It was a public relations exercise as well as a legislative exercise.”

Over in the U.S. Senate, Richard Lugar of Indiana and Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, co-sponsored the bill to grant Chrysler’s wish. Lugar, a Republican, had Chrysler plants in his state. Tsongas, a Democrat, believed in keeping the national economy strong. Joe Biden wanted to save Chrysler jobs in Delaware. Michigan Sens. Don Riegle and Carl Levin, both Democrats, urged colleagues to support the effort.

The UAW led by President Doug Fraser worked hard to gin support for Chrysler, and many Democrats felt loyalty to the labor union because of its civil rights record. Walter Reuther helped finance the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, formed after the Montgomery bus boycott that followed the arrest of Rosa Parks in 1955.

“When you look at the march on Washington, you’ll see photos of Reuther locking arms with King,” Blanchard said. “It was very significant.”

All factions focused their attention on the U.S. House, knowing it was critical to the process, Blanchard said. “The U.S. Senate was not going to take it up unless the House passed it first. Congress did the right thing for the right reasons, even though it was unpopular.”

In addition to Treasury Secretary Miller, Carter dispatched Vice President Walter Mondale, Assistant Treasury Secretary Roger Altman, Chief White House Domestic Policy Adviser Stuart Eizenstat and Assistant Domestic Policy Adviser David Rubenstein to secure a $1.5 billion loan guarantee to keep Chrysler in business, not including sacrifices made by employees, states and financial institutions.

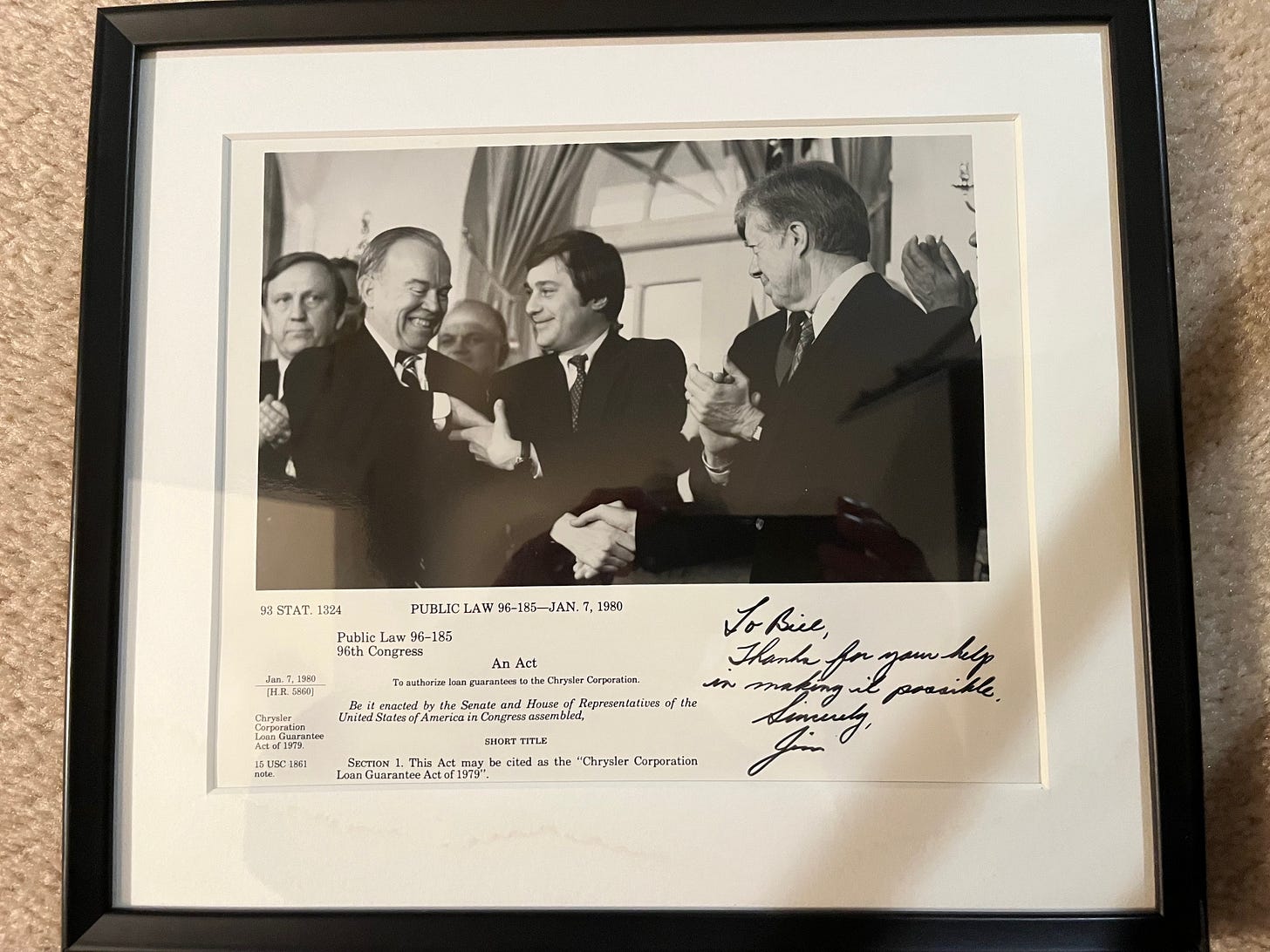

The House passed the deal at the end of December and the Senate followed shortly thereafter. Carter signed the rescue package in early January 1980. Blanchard stood behind the president as the only Michigan member of the House Banking Committee who helped guide the process.

“He gave me the first pen,” Blanchard said.

UAW taps governor to be their voice

The legacy of relationships forged during the Chrysler bailout carried through Michigan politics for decades.

The high-profile victory built on diverse coalitions catapulted Blanchard’s career. Democrats created a movement to draft him to run for governor, and he served from 1983 to 1991. Blanchard said that had never been his plan.

After Chrysler and General Motors filed for bankruptcy in 2009, then-President Obama worked to help them recover. As the automakers created new boards of directors, then-UAW President Ron Gettelfinger asked Blanchard, then a former two-term governor and four-term congressman, if he would take the board seat designated for labor representation..

“I said to Gettelfinger, ‘What do you want me to do? What do you expect?’ He said we’re not going to tell you what plant to open or close or anything. We’re not going to do any of that. We want them to survive and make a profit,’” Blanchard said. “‘You saved us once before, you’ll help save us again’ is what Ron Gettelfinger said. He did say that.”

The UAW announced Blanchard’s role to the world the next day.

“I worked three years with Sergio Marchionne, from 2009 to 2012,” Blanchard said. “He was as smart as any auto executive I’ve ever met.”

After all these years, Blanchard has kept a detailed diary with dates, times and places. He consulted his notes during the interview.

Looking back, Carter never took enough credit for helping Michigan, Blanchard said. “He should have. He never did.”

PS: As a proud member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative, a roundup of world-class journalists, I hope you’ll check out the incredible collection of columns that include news, commentary and features.

Wow. What a great behind-the-scenes story from people who were there. Blanchard was a so-called Watergate baby.

Phoebe, thanks for a great story. The events of the multiple auto bailouts would make a good podcast.